Semester:

Offered:

Course Description: Digital and social media platforms have brought about rapid and fundamental changes in the political landscape of our digital age. While those new technologies shape the ways we perceive and read the world, gather information, communicate with others, shape public opinions, and make political judgments, the institutional and electoral arenas have lost the monopoly of political decisionmaking. Instead, there now exist multiple levers to make political influence. Amidst this very change, young people rise as key political actors and re-write the meaning of political. This course will introduce students to an array of research and concepts that help clarify the political landscape in a digital age, as well as inviting them into close consideration of a set of design principles to guide effective, equitable, and self-protective civic agency in the contemporary communications environment. Student engagement and active inquiry in class is crucial. For a group project, students will conduct case studies to connect theory with practice and share their knowledge with their peers.

Case Study -- "Own Your Knowledge"

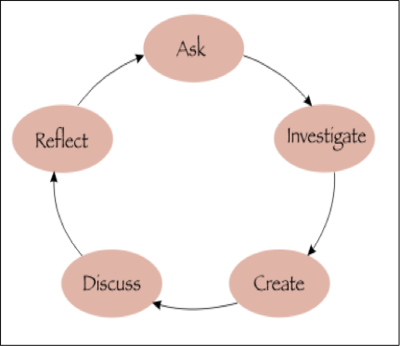

Case study is a signature project for Gov94CZ. Students choose a case (any group, any organization, or any single person) that matters to them, and they investigate their cases using the Ten Questions. Students situate their case in the theoretical context discussed in class. In fall 2016, Students brought cases from all different corners of the participatory politics terrain: Veganism, Reclaim Harvard Law School, Get Out To Vote (GOTV), and Harvard Civics Program. "Own your knowledge." We want students to create their own meanings from their experiences both in and beyond class. Lecture and readings are important, of course. But they are not the best way to own knowledge. Connecting theories, knowledge, and practices you hear from the class to your lived experiences begins with an authentic question that matters to you. Simply, what do you care about? And why does it matter to you? It does echo the first principle of the ten. Then, how do you proceed to the next steps? You engage in the inquiry cycle originally drawn from John Dewey. Once you come up with an essential question that connects with your life, you can investigate through multiple methods, sources, and media. Any tangible products can derive from investigation––the tangible product in our class will be your case study. Note that your creation is inseparable from other steps, especially discussion and reflections. You need to discuss meanings and lessons of your creation with others and then go back to previous steps, namely investigation and creation, and tinker with your creation. In the end, you and your audience––now your instructors and peers but beyond that down the road––are all invited to a broad vista to “look back” at the whole inquiry process and generate further meanings together. These five steps, of course, are neither linear nor discrete. Rather, they are embedded in one another. The point here is that this inquiry cycle can break down your inquiry processes––typically complicated and less articulate––into small pieces and monitor your own meaning making experiences. In completing this process you claim the ownership of knowledge. Though the knowledge is provisional and tentative, you can own it for a moment. Please see the related posts: “The YPP Action Frame with Inquiry-Based Learning II: "Small Inquiry" and "Big Inquiry"” and “The YPP Action Frame with Inquiry-Based Learning I: An Inquiry Cycle” from the YPP Action Frame site. How Students Conduct Case Study? Team up with your peers (2 or 3 students in one group) to conduct a case study. What kind of case study? You could start by writing a captivating story around the case. We will discuss several real world cases during class, and you can imagine emulating one of them. The case study can be like a journalistic report in which the story can be situated in particular theories and perspectives we discuss in class. The cases we address there are quite lengthy, but you are not necessarily required to write such a long paper. What matters most is the content and message you want to deliver through the case; this project is an exercise both to express your creativity and practice research skills. It is broken into small pieces (P1, P2, P3-1, P3-2, and P3-3) to help you complete the end project (P4) effectively.

|

Link:

| gov_94_cz_syllabus_fall_2016.pdf | 413 KB |